Lazy loading of snapshot restores and its implications on database performance

This post talks about volume snapshots with AWS as an example, but the concepts are generic and can be applied anywhere.

Managed Databases

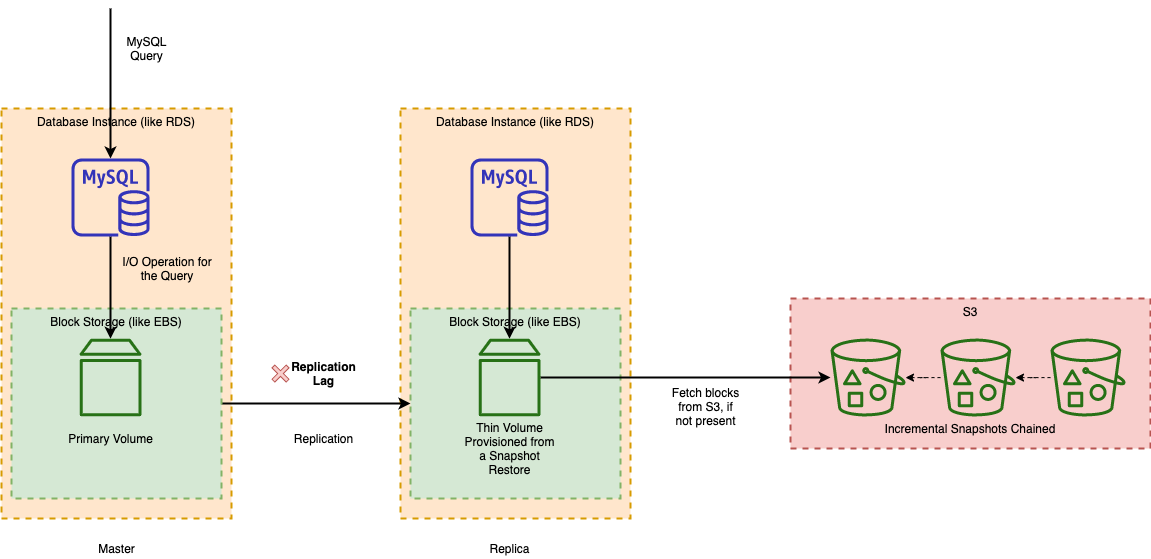

Most of us use managed databases in the cloud today for our applications, like MySQL or PostgresSQL. Behind the scenes, a cloud provider, like AWS, takes care of operations such as provisioning, monitoring, failover, backups, and restores of the database instances with their RDS or Aurora like offerings. In this post, I’ll be specifically covering how backups and restores of stateful services like RDS work behind the scenes and the gotchas you should be aware of.

Persistent Storage of Database Instances

A database instance like MySQL or PostgresSQL normally uses a storage volume on which the data directory is mounted.

Snapshots of Storage Volumes

Irrespective of the type of storage being used by RDS or Aurora, they both support backups of your database instances. These backups are snapshots of the volume on which the data directory is mounted. The following happens when a backup is taken.

Locking the Filesystem

Before a snapshot of a volume is taken, it’s important to block new writes to the filesystem, so that the snapshot of the underlying volume is in a consistent state.

Flushing the Filesystem

Most of the time, the operating system doesn’t do sync writes to the non-volatile storage, rather it caches it in the page cache for performance reasons unless otherwise specified by the application or the database.

MySQL supports locking and flushing through the

FLUSH TABLES WITH READ LOCKcommand

Taking the snapshot

The point-in-time backup or snapshot includes the actual copying of the data blocks. These snapshots can be full or incremental. With incremental snapshots only the data blocks which have changed since the last snapshot are copied. This helps with faster snapshots or, in other words, with reducing the Recovery Point Objective.

Unlocking the Filesystem

Once the snapshot is taken, the filesystem can be unlocked and normal operations, including writes, can now continue. For example, MySQL UNLOCK TABLES command can help achieve this.

Full vs Incremental Backups of Snapshots

As mentioned before, a snapshot can be a full backup or an incremental backup. Internally, the snapshots can be chained together. AWS keeps all the snapshots in S3 buckets. More details on incremental EBS snapshots by AWS can be found here

Restoring Snapshots and Lazy Loading

When a snapshot is restored, the restored database instance can be used as soon as the status is available. The DB instance continues to load data in the background. This is known as lazy loading.

As the name suggests lazy loading fetches data blocks from S3 only on-demand when a query is unable to locate the requested data blocks.

AWS also recommends doing a full table scan, such as SELECT * to mitigate this problem, which, in my opinion, is not suited for large production databases.

The reason why a database instance with a thin volume is made available for operations without loading all the data blocks pro-actively is to again reduce the Recovery Time Objective and lazy load the blocks on-demand.

Impact of Lazy Loading on Database Operations

Now, we know that the strategy of incremental snapshots with lazy loading helps in reducing both RPO and RTO, in case of a disaster. But it comes with a tradeoff, which is performance and it causes an increase in latency since data blocks of a restored snapshot are fetched on-demand from S3. Let’s look at what specific problems this can create for a large production database which may already be under load.

Slow queries in the Master Restored from a Snapshot

If you choose to provision a master database instance from a snapshot restore, it can cause slow queries, as an EBS volume fetches data blocks from S3 on-demand.

Replication Lag in the Replica Restored from a Snapshot

Similarly, if you choose to provision a replica or a slave from a restored volume, it can cause replication lag due to the replication process being slow again due to on-demand fetching of data blocks from S3.

Fast Snapshot Restore (FSR) in AWS

AWS also introduced EBS Fast Snapshot Restore (FSR) in 2019 to overcome the performance issues with lazy loading, but under the hoods, FSR just provisions extra resources to deliver the fast restores, proceeding at a rate of one TiB per hour. By contrast, non-optimized volumes retrieve data directly from the S3-stored snapshot on an incremental, on-demand basis.

FSR, again does not completely solve the problem, but only mitigates it to some extent by throwing more resources at the problem and proactively hydrating the volume instead of on-demand hydration. Multi TB database volumes would still take hours to completely hydrate with FSR.

Summary

Incremental snapshots with lazy loading while restoring is a necessary evil IMO, to reduce the RPO and RTO, but the performance impact which comes with it cannot be ignored. It’s important to be aware of these gotchas, especially with large databases. More importantly, AWS provides no visibility into the hydration status of a volume, in terms of the percentage of blocks hydrated or the rate at which hydration is happening etc. which makes it worse.

References

- https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonRDS/latest/UserGuide/USER_RestoreFromSnapshot.html

- https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AWSEC2/latest/UserGuide/EBSSnapshots.html

- https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonRDS/latest/AuroraUserGuide/Aurora.Managing.Backups.html

- https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/aws/new-amazon-ebs-fast-snapshot-restore-fsr/